THCon 2025 Prechallenge – Printf Weird Machine

As usual, the 2025 edition of THCon included the Prechallenge, a major CTF challenge that lasts one month, featuring high difficulty but cool rewards.

THCon is mostly organized by the French "TLS-SEC" master's program, and as a participant in it, I decided to tackle one of the steps in the prechallenge. My goal was to build a weird machine based on the C function printf(). This idea was inspired both by one of the winners of the 2020 IOCCC, who created a working Tic-Tac-Toe game using only printf() (Nicholas Carlini), and by my love for weird machines and architectural design.

A full write-up of the Prechallenge was presented at THCon by its creator, Benoit Morgan, and the winner, Crazer.

But let’s focus on the printf() step. :)

The Challenge: "YetAnotherSimpleKeyGen"

This step was the last one of the Prechallenge, and is very straightforward; you are given classic elf binary that asks you to input a "password" to validate the challenge.

➜ ./YetAnotherSimpleKeyGen

usage: ./chall <secret>

➜ ./YetAnotherSimpleKeyGen BadPassword

Try harder >:3

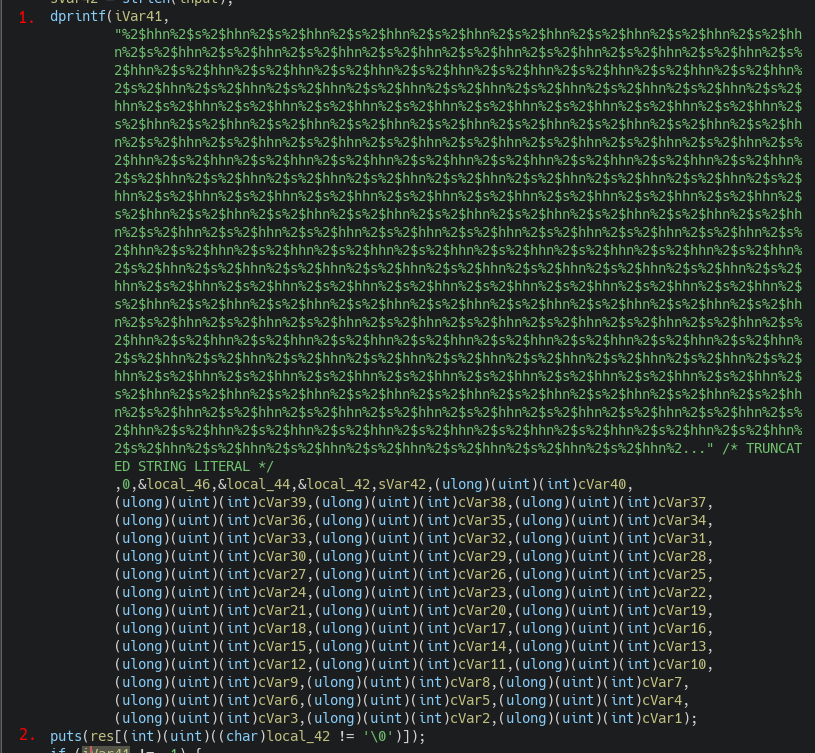

Naturally, the player would analyze the program further, perhaps decompiling it:

The C program is fairly simple:

- It contains a large call to

printf()with a format string a couple of thousand characters long. - Then, it uses

puts()to print one of two strings, depending on whether the password was valid or not.

Surprisingly, there's no conditional statement to check whether the password is valid. All of the logic is embedded within the printf() call.

The weird machine itself :

Like all programs, this VM can be divided into two segments, code and data:

- The code segment contains the format string, since this is a printf()-based VM, this is the only type of code allowed.

- The data segment consists of all the arguments passed to the format string, including both registers and plain data.

The main challenge was to implement a VM that runs within a single printf() call, much like Nicholas Carlini’s print-tic-tac-toe. This limits how we can perform write operations and makes debugging especially hard, since the VM operates in a single state.

Data & Types

Registers

The VM employs two types of registers.

1. Core Registers (16-bit)

The core registers are 16-bit registers that printf() can interpret as either strings or integer values. To print them as strings, the second byte is always 0 (effectively a null terminator). As a result, printing a register with printf() will always output a single character, or nothing at all if the first byte is also 0.

Since the second byte is never actually used, the effective reference value of a register is 256.

char register[2] = {0, 0};

These registers can be printed using two formats :

- As strings

%1$s - As integers

%1$.*1$d.

The string format is ideal for binary operations: when the register is zero ({0, 0}), we print 0 characters; when the register contains a value ({<1,255>, 0}), we print one character.

The integer format allows us to print X characters in the output, where X is the register's value. For example, a register with the value {100, 0} will print 100 characters.

2. Constant Registers

The second type of registers are constants, these are instantiated as regular C integers before the VM starts.

int register_constant = 42;

RAM

The VM also includes raw data stored in its memory, such as the password provided by the user. This data is passed as arguments to the format string, making it accessible to the VM during execution.

We can tell the difference between registers and raw data by how they are handled in memory. Registers are pointers to data that already exists on the stack before the VM starts running. In contrast, memory values like user input are copied directly onto the stack specifically for the printf() call.

Memory Access

There are two methods to access data: direct and pointer-based.

Direct Access

With direct access, the compiler places data directly in the code segment explained earlier. For example, to print 3 characters via direct access, the compiler generates this macro:

printXFromLitteral(3)

Which yields "%1$3d" (data is in the code)

Pointer Access

Pointers are situated, in the data segment.

For example if the VM needs to access the second register (second parameter), the code would index the second argument (using 2$) and printf() would do the dereference. eg :

printXFromPointer(2)

This results in "%2$.*2$d" (data is in the VM's RAM)

Executing Multiple Operations in a Single printf() Call

A major challenge in running the VM entirely within a single printf() call is how to manage memory write operations correctly.

Consider this example: we want to write the value 3 into reg1 and the value 2 into reg2:

printf("AAA%nBB%n", reg1, reg2);

At first glance, this might seem fine. However, there's a hidden problem: the %n format specifier writes the total number of characters printed so far to the given address. In this case:

- reg1 receives 3 (for the three 'A' characters).

- reg2 receives 5, not 2; because the count continues after the first %n.

This cumulative counting makes %n unreliable for writing independent values.

The Solution: Controlled Writes with %hhn

To solve this, a technique discovered by Nicholas Carlini uses integer overflow with the %hhn format specifier. Unlike %n, %hhn only write into the lowest byte of given pointer, this prevent the data written to be bigger than 255.

Now, we need a way to reset the internal character counter of printf() to write arbitrary data using %n. To do that, the VM uses a control register called ctrflag, that keeps track of the total number of characters printed so far. Here is an example :

printf("AAA%hhnBB%hhnCC%3$hhn", reg1, reg2, ctrflag);

// reg1 = 3

// reg2 = 5

// ctrflag = 7

Resetting the Character Counter to a Multiple of 256

Making an iterator

To prevent the counter from growing indefinitely (and interfering with future writes), we want to reset it to 0 using byte overflow. Here's how it's done:

printf("%1$s%1$hhn", ctrflag);

%1$sprints thectrflagas a string (so it outputs one character, or nothing if the first byte is 0).%1$hhnwrites the total number of bytes written so far (mod 256) back to the same address.

For a better representation :

if (ctrflag)

ctrflag++;

Ensuring a True Reset

To guarantee a reset regardless of the starting value, this format is repeated 256 times. Eventually, the cumulative count overflows and lands on a multiple of 256; effectively resetting the counter to zero.

Here’s a macro to represent that:

#define resetCounter(ctrflag) "%"#ctrflag"s%"#ctrflag"hhn" // imagine this format string repeated 256 times

The Poc :

printf("AAA%1$hhn" resetCounter(3) "BB%2$hhn" "%3$hhn", reg1, reg2, ctrflag);

Results in:

- reg1 = 3 (from "AAA")

- reg2 = 2 (actually 258, but %hhn keeps only the lower byte → 258 % 256 = 2)

- ctrflag = 2 (same overflow logic applies)

VM Workflow

Once you have understood all the VM's internals, the workflow is very simple. The VM just walks through the password and verifies the value of each character using simple reversible operations such as add and sub and direct match.

If one the characters is wrong, the VM will populate a cflag, that will be used to print the right message to the player.

Made with luv :3