HTB Virtually Mad

Virtually mad was a very interesting challenge, I was very new to ghidra and it made me push more its functionalities

Difficulty : Medium

Category : Reversing

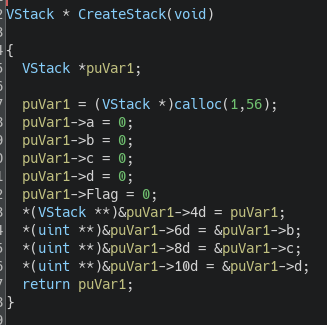

For this challenge I relied on three main tools: Ghidra, gdb, and the decomp2dbg plugin. The plugin integrates Ghidra with gdb, which is useful during debugging since gdb can show a decompiler view of the code. More importantly, gdb can import symbols from Ghidra, letting you set breakpoints and disassemble functions or variables identified by the decompiler.

First inspection

First, I did a simple file check on the binary:

$ file virtually.mad

virtually.mad: ELF 64-bit LSB pie executable, x86-64, version 1 (SYSV), dynamically linked, interpreter /lib64/ld-linux-x86-64.so.2, BuildID[sha1]=27b0820aa0b06b1dd720035f2e736a1a623d4450, for GNU/Linux 4.4.0, stripped

It's a standard stripped ELF. Let's run it:

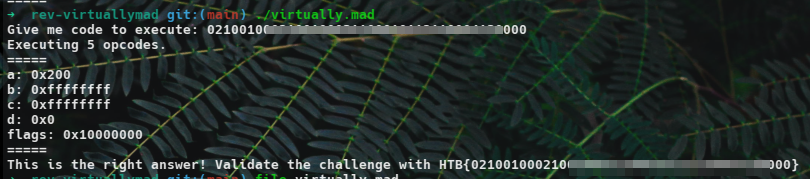

The program "asks" for code to be executed, later referred to as "opcodes". At this point, I suspected it was some sort of emulator that we would need to reverse. Let's launch it in Ghidra:

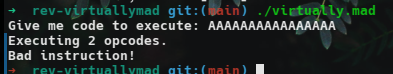

Here is the main() function. At the top of the decompiler output the program reads a string from the user and enforces a minimum length of 8 bytes. It then processes the input as an array of 8-byte blocks (input_size >> 3) and iterates over the buffer in those fixed-size chunks. For each chunk the code extracts an opcode, parses it as an unsigned integer in base 16, and performs validation checks. Only the first five opcodes are parsed and validated, which suggests that supplying five correct opcodes should be sufficient to obtain the flag.

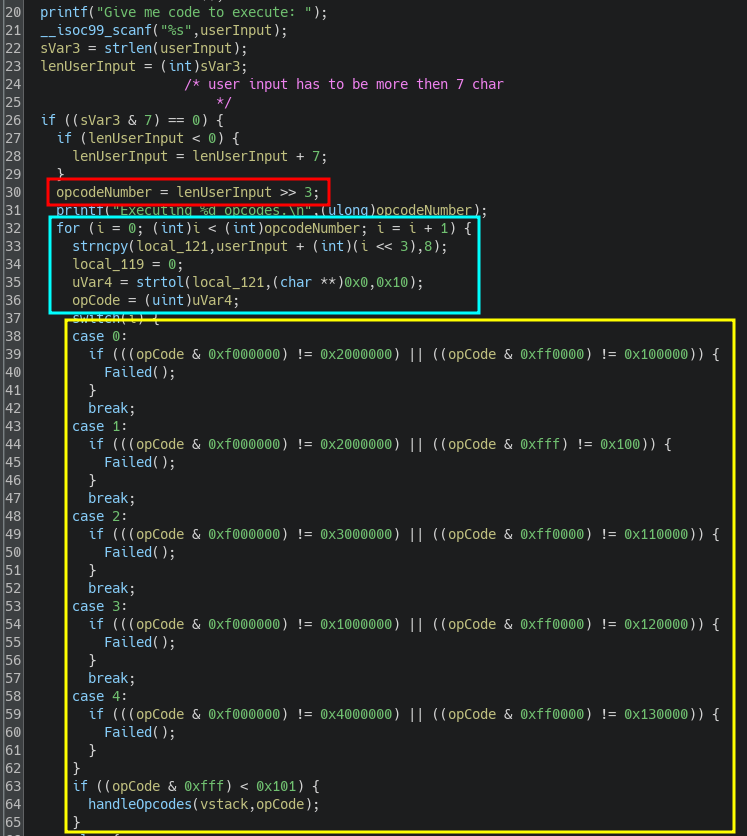

As seen in the screenshot, the function handleOpcodes processes the opcode and references a variable I named "vstack" (short for "Virtual Stack"). This took me some time to understand, but since the program emulates opcodes, it also emulates a stack or at least registers to push and pop data from. This variable is declared just before the screenshot of the main(), in this function:

The VStack is an array of 14 integers and seems to store 4 registers (which I'll later name reg_{a,b,c,d}) and a flag, which will later serve as a Carry Flag. I created a struct called VStack to better understand how the program references registers.

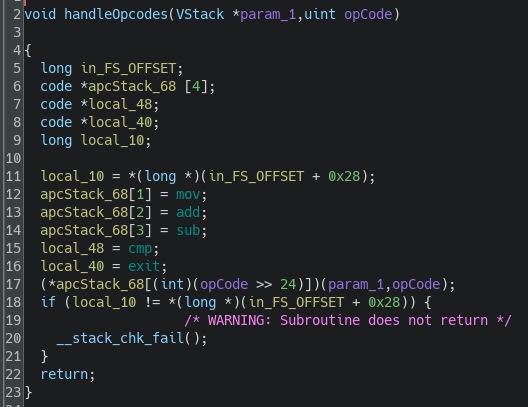

Let's now take a look at handleOpcodes:

We can see that the program creates an array of function pointers, which were identified as the actual opcodes functions: mov, add, sub, cmp, and exit. These functions are called using the value encoded in the higher byte of the opcode.

The decompiler view looks odd because I believe these 5 functions pointers were embedded in a struct. Let's now examine the mov and cmp instructions to understand how the instructions work; the others follow a similar structure.

If we consider our opcode in binary as follows:

0000 0000.0000 0000.0000 0000.0000 0000

We can assign names to the nibbles of the opcode like this:

1 2.3 4.5 6.7 8

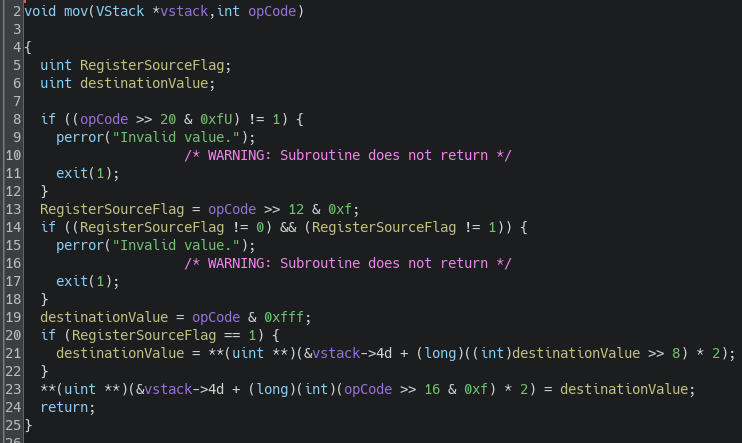

The mov function checks different values in the opcode:

1. Nibble 3 must have the value 1.

2. Nibble 5 must have the value 0 or 1.

3. Nibble 4 seems to reference a register.

4. Nibbles 6, 7, and 8 seem reserved for an arbitrary value encoded on 12 bits.

If nibble 3 has the value 1, the function retrieves the value of a register and places it in the register specified by nibble 4. If nibble 3 is 0, it moves the value from the last 3 nibbles into the register.

In pseudo-code, this function would look like this:

value = nibble678

if nibble5 == 1:

value = register_pointed_by_nibble678

register_pointed_by_nibble4 = value

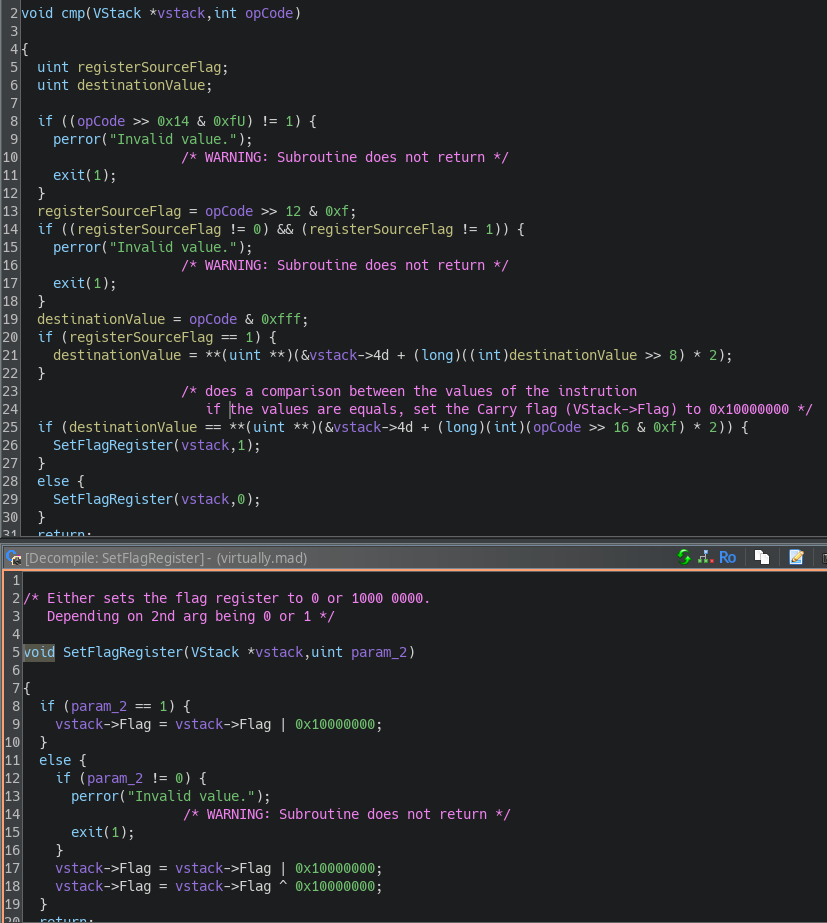

Let's now look at the cmp instruction:

The logic of cmp is quite similar, with one key difference. Depending on the result of the comparison in line 25, the function calls SetFlagRegister, which sets the Flag variable of our VStack to either 1 or 0, depending on whether the comparison is equal. I believe this is equivalent to the Carry Flag in assembly.

Now that we understand the overall functionality of the instructions, we can define the structure of an opcode as follows (in nibbles):

AlwaysZero InstructionCode AlwaysOne DestReg RsFlag Value(on 3 nibbles)

Getting the Flag

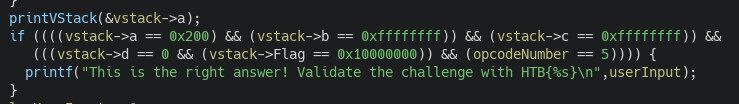

Let's now look at what we need to do to get this damn flag !

We need the following values to get the flag:

- reg_a = 0x200

- reg_b = reg_c = 0xFFFF FFFF

- reg_d = 0x0

- Flag = 0x100 0000

But we also have some constraints:

- The value must be less than 0x101

- We need to execute ADD -> ADD -> SUB -> MOV -> CMP in this specific order.

- The instruction must reference the registers reg_a -> ___ -> reg_b -> reg_c -> reg_d in this specific order.

So I came up with the following order of instructions:

// set a to 0x200

ADD $a 256

ADD $a 256

// set b and c to 0xFFFF FFFF

SUB $b 1

MOV $c $b

// set Carry flag to 0x1

CMP $d 0

Because I was having a hard time crafting my shellcode manually, I wrote a Python program to abstract this process:

# Define instruction constants as nibbles

MOV = 0x1 # 1 in hexadecimal (0001)

ADD = 0x2 # 2 in hexadecimal (0010)

SUB = 0x3 # 3 in hexadecimal (0011)

CMP = 0x4 # 4 in hexadecimal (0100)

EXIT = 0x5 # 5 in hexadecimal (0101)

# Define register constants as nibbles

REG_A = 0x0 # Register A (0000)

REG_B = 0x1 # Register B (0001)

REG_C = 0x2 # Register C (0010)

REG_D = 0x3 # Register D (0011)

# Constants for always zero and always one nibbles

ALWAYS_ZERO = 0x0

ALWAYS_ONE = 0x1

# Define the OpCode class to work with nibbles

class OpCode:

def __init__(self, instruction_code, dest_register, *args):

# The opcode will be a stream of 8 nibbles (32 bits total)

self.opcode = [ALWAYS_ZERO, instruction_code, ALWAYS_ONE, dest_register]

# If there's one argument, it's treated as an immediate value encoded over 3 nibbles (12 bits)

if len(args) == 1:

value = args[0] & 0xfff # Mask to fit into 12 bits (3 nibbles)

self.opcode.append(0x0) # Set RsFlag

self.opcode.append((value >> 8) & 0xF) # Most significant nibble

self.opcode.append((value >> 4) & 0xF) # Middle nibble

self.opcode.append(value & 0xF) # Least significant nibble

# If there are two arguments, it's register-to-register

elif len(args) == 2:

source_reg = args[0]

is_source_reg = args[1]

# Append the source register or value and the flag

self.opcode.append(0x1 if is_source_reg else 0x0)

self.opcode.extend([source_reg, 0x0, 0x0]) # Extend to handle full 3 nibbles

# Padding to ensure the opcode has exactly 8 nibbles

while len(self.opcode) < 8:

self.opcode.append(0x0)

def to_bytes(self):

# Convert nibbles into bytes for shellcode (2 nibbles per byte)

return ''.join(f'{(self.opcode[i] << 4 | self.opcode[i + 1]):02x}' for i in range(0, len(self.opcode), 2))

def labeled_view(self):

# Create a labeled view of the opcode with nibbles and their categories

categories = [

"AlwaysZero", "InstructionCode", "AlwaysOne", "DestReg", "RsFlag", "Value"

]

labeled_output = []

for i in range(len(self.opcode)):

if i == 5:

labeled_output.append(f"{categories[i]}={self.opcode[i]:04b} {self.opcode[i+1]:04b} {self.opcode[i+2]:04b}")

break

labeled_output.append(f"{categories[i]}={self.opcode[i]:04b}")

return ' '.join(labeled_output)

# Function to generate binary stream and shellcode

def generate_opcode(opcodes):

binary_stream = ""

shellcode = ""

for opcode in opcodes:

# Generate the binary stream (4 bytes formatted as 8 nibbles)

binary_stream += ''.join(f'{nibble:04b}' for nibble in opcode.opcode) + "\n"

# Generate shellcode (hex)

shellcode += opcode.to_bytes()

return shellcode

def main():

# Example: ADD reg_a, 256 and MOV reg_b, reg_a

opcodes = [

OpCode(ADD, REG_A, 256),

OpCode(ADD, REG_A, 256),

OpCode(SUB, REG_B, 1),

OpCode(MOV, REG_C, REG_B, True),

OpCode(CMP, REG_D, 0)

]

# Generate and print the binary stream and shellcode

shellcode = generate_opcode(opcodes)

print("\nShellcode:")

print(shellcode)

# Print labeled view for each opcode

print("\nLabeled View of Opcodes:")

for opcode in opcodes:

print(opcode.labeled_view())

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()

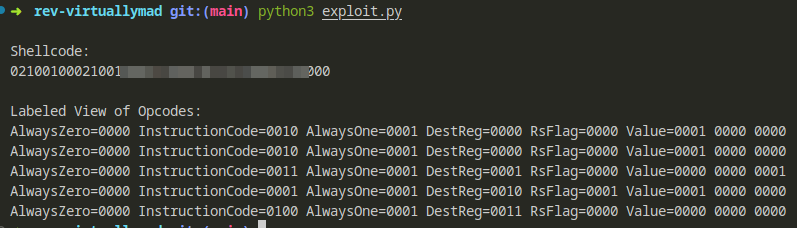

Which gave me this output :

And got validated !